Guided Visits

Guided visits through the exhibition “Helmut Newton. Polaroids” with Hans-Michael Koetzle.

Starting time is 6pm, lasting until approximately 7:30pm. Participation in the tours is free.

No prior registration is necessary.

Guided Dates:

Fri: 17.10.25

Fri: 21.11.25

Fri: 5.12.25

Fri:, 12.12.25

Fri: 9.01.26

Fri: 16.01.26

Fri: 30.01.26

Fri: 6.02.26

Fri: 20.02.26

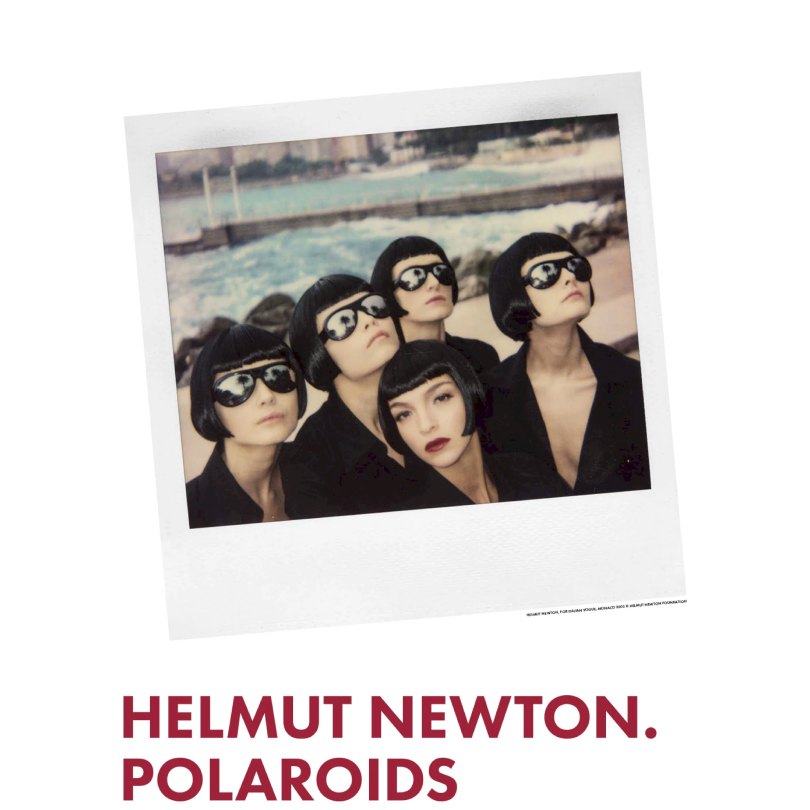

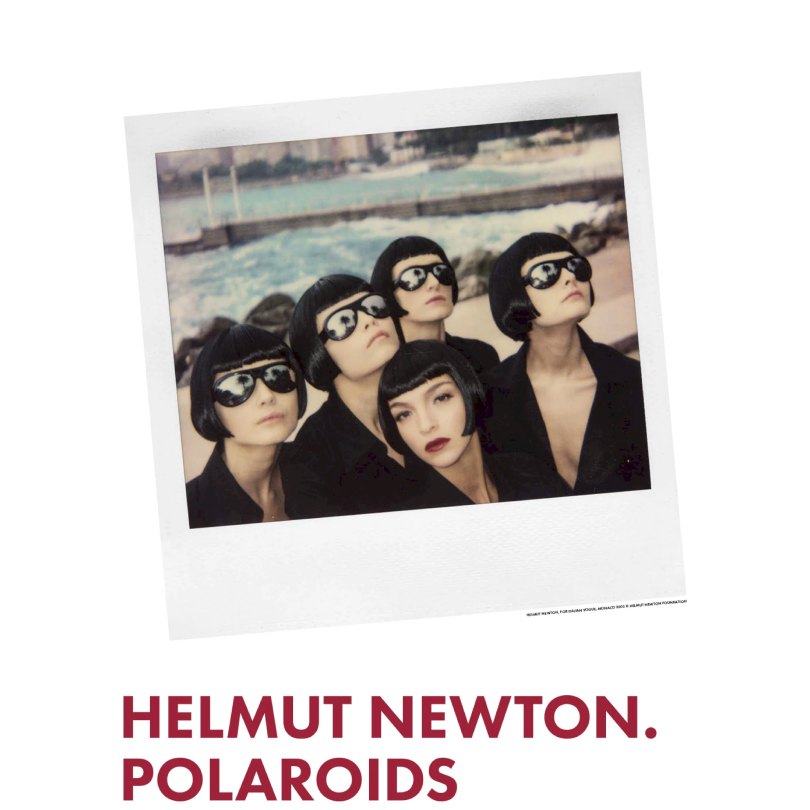

Starting on 15 October 2025, the Kunstfoyer of the Versicherungskammer Cultural Foundation in Munich will present the exhibition “Helmut Newton. Polaroids.” The exhibition showcases iconic instant photographs by the renowned photographer, capturing Newton’s unmistakable style in a spontaneous medium.

Since the 1960s, the Polaroid process has revolutionized photography. As early as 1947, Edwin Land developed instant photography for his company, the Polaroid Corporation, based in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Over the years, many acclaimed photographers tested and continuously refined the technique on behalf of the company. This led to the first exhibitions, a dedicated artistic support program, and the foundation of the Polaroid Collection. Naturally, Helmut Newton is represented in this collection with several works.

Anyone who has ever used this camera will remember the smell of the developing emulsion, the speed of the image emerging — the fascination of instant photography. With the particularly popular SX-70 camera, the Polaroid print developed on its own; the developing and fixing chemicals were already embedded in the photographic paper, and the image was ejected through a narrow slot at the front of the camera. Other Polaroid processes required users to apply a fixing fluid across the surface of the photograph. In nearly all cases, the finished image could be held in one’s hands immediately after exposure, allowing instant review of the composition. In this sense — not technically, but in terms of immediacy — Polaroid photography can be seen as a precursor to modern digital photography, whether on smartphone displays or digital cameras.

Polaroids are, in most cases, unique objects. Only certain films, especially black-and-white ones, produced negatives that some photographers enlarged as small-edition silver gelatin prints. For some, Polaroids served as visual preliminary studies; for others, they were standalone works of art. From the 1960s onward, this unusual technique won enthusiasts across all genres — advertising, landscape, portrait, fashion, and nude photography — and across the globe, both in applied and artistic photography.

Helmut Newton, too, made intensive use of different Polaroid cameras, especially during his fashion shoots. Behind this lay, as he once said in an interview, an impatient desire to know immediately how a situation translated into an image. The Polaroid acted as a kind of sketch; at the same time, it helped verify the specific lighting and composition. Often only a few Polaroids were enough for his initial inspection; only for his “Naked and Dressed” series for Vogue did he use the material “by the crate,” as Newton himself put it.

The exhibition at the Kunstfoyer of the Versicherungskammer features roughly equal numbers of individually framed SX-70 or Polacolor prints and mounted Polaroid enlargements — more than 150 works in total. Since the 1960s, Newton had worked with various Polaroid cameras and also used instant-film backs that replaced the roll-film cassettes of his medium-format cameras. Looking at his Polaroids — which stood at the beginning of almost every fashion image he created and in which his incomparable visual ideas first took shape — we can trace the concepts that he later elaborated into the final images he approved. Two examples demonstrate the progression from photographic sketch (via Polaroid) to the final image shot afterward with an SLR camera on “real” film, as he always insisted. Thus, during the exhibition tour, the origins of many other iconic images — published in his books and firmly embedded in our collective visual memory — become visible along the way. In this sense, the exhibition offers a glimpse into the sketchbook of one of the most influential photographers of the 20th century.

In 1992, Newton published Pola Woman with Schirmer/Mosel — an unusual book consisting exclusively of his Polaroid photographs. As he noted, the publication was “especially close to his heart,” yet it sparked controversy. Critics complained that the images were not polished enough, to which he replied: “But that was exactly what made them exciting — the spontaneity, the immediacy.” Some of his Polaroids were later published in magazines, and certain signed prints now fetch high prices on the art market. Posthumously, in 2011, the Helmut Newton Foundation in Berlin published another book of his Polaroids with Taschen.

Newton’s handwritten notes along the image margins are particularly interesting and revealing — occasional comments about the model, the client, or the place and date of the shoot. These written remarks, along with the blurriness and wear marks, also appear on the Polaroid enlargements shown in the exhibition. They reflect the pragmatic use of these original working materials, which have since acquired an autonomous artistic value. The unique aesthetic of Polaroids — which can unpredictably alter colors and contrasts — continues to make this experimental technique compelling today. Newton used his Polaroid cameras for decades across nearly all areas of his work, though least often for portrait sessions. Some of the small-format originals he gave to clients or models, as he put it, to secure their “cooperation.” Most he guarded like a treasure, now preserved in full within the foundation’s archive.

A display case also contains various Polaroid cameras for smaller image formats from a private collection in Berlin; their diversity in shape, design, and features reflects both the playful engagement with the medium and its popularity. And the fascination for this extraordinary technique continues, even though the successor films by “Impossible” are often said not to match the quality of the original Polaroid materials. Resourceful contemporary photographers still seek out the last remaining expired original film stock available on the market and experiment with it. Many of these contemporary Polaroids — often serial, arranged as tableaux, or abstract — possess a unique visual reality as one-of-a-kind prints. Newton, however, used Polaroid film primarily as a means to an end, yet his photographic sketches nevertheless led to exceptional, independent visual solutions.

Matthias Harder